Note: I initially set out to write a release announcement for Elmstatic, but then I thought: "What the heck, I might as well explain how to actually use elm-markup". So most of this post turned out to be an elm-markup tutorial. Still: Elmstatic now supports elm-markup!

Markdown is a fine option for writing the content of a static site built with Elmstatic, but it falls short in some scenarios. While the Elm compiler will helpfully report errors in your page layout (because it's written in Elm), you will not get told about any issues with your Markdown.

In addition, Markdown is good when you have pages of mostly text, but it becomes inconvenient when you need more complex forms of content, if you assemble pages from reusable parts and so on. You have to start inserting fragments of HTML and coming up with other workarounds.

Finally, Markdown becomes difficult to combine with views implemented in elm-ui (in particular, styling is somewhat problematic). I should point out, however, that elm-ui is only useful for a static site if you don't need it to be responsive.

There is another markup option in Elm-land!

mdgriffith/elm-markup is an interesting package that allows you to take marked up text, and transform it into the output format of your choosing. It's recently been updated to version 3.

The markup looks like this:

|> Metadata

title = Elmstatic now supports elm-markup

tags = software other

*Elmstatic* now supports `elm-markup`{name}!

|> H2

Let's look at some /code/

Code is highlighted using [Highlight.js]{link | url = https://highlightjs.org}:

|> Code

lang = elm

code =

view =

\content ->

{ title = ""

, body = [ htmlTemplate content.siteTitle <| view content ]

}

Matt has also created a VS Code extension which provides syntax highlighting and checking for .emu files.

There are two benefits compared to Markdown:

- When a document is parsed, you get parsing errors describing what's wrong.

- The markup is highly customisable: in your Elm code, you define a parser for all of the blocks starting with an arrow (

|> Metadata,|> H2and so on), as well as the inline formatting (such as[Highlight.js]{link | url = https://highlightjs.org}).

Elmstatic can now handle .emu files

I've previously shown how elm-markup can be used with Elmstatic by simply substituting the Markdown text with elm-markup text.

However, that was a bit of a hack, so now I've extended Elmstatic with proper support for elm-markup.

Right now, for example, if you use a non-existent markup block like |> H4, Elmstatic will report an error:

Error in _pages/about.emu:

UNKNOWN BLOCK

I don't recognize this block name.

4|> H4

^^

Do you mean one of these instead?

H3

H2

H1

Code

List

Image

It's also possible to go beyond detecting parsing errors, and verify other aspects of the content — for example, whether relative links are valid, or whether block attributes satisfy particular constraints. I might explore this in future releases.

How to create an elm-markup site

To start an elm-markup site, run the following:

$ npm install -g elmstatic

$ mkdir my_project && cd my_project

$ elmstatic init --elm-markup

$ elmstatic watch

Elmstatic will create a scaffold with some basic elm-markup parsing included. As usual, you are free to modify all your Elm code to suit your needs, including defining all the elm-markup blocks and inline formatting that you want.

When you run elmstatic watch, Elmstatic will watch all the source files for changes and rebuild the site, reporting errors in your layouts and your

.emu markup files, if there are any.

That's it!

But how can elm-markup be parsed?

You will probably want to customise your elm-markup at some point. I wanted to show you a few quick examples, but I went overboard and ended up writing a full-blown tutorial! Read on to find out how to construct elm-markup parsers.

Consider the markup example I showed above:

|> Metadata

title = Elmstatic now supports elm-markup

tags = software other

*Elmstatic* now supports `elm-markup`{name}!

|> H1

Let's look at some /code/

Code is highlighted using [Highlight.js]{link | url = https://highlightjs.org}:

|> Code

lang = elm

code =

view content =

{ title = ""

, body = [ htmlTemplate content.siteTitle <| toHtml content ]

}

There are many elements here:

- Named blocks with attributes such as

|> Metadataand|> Code, or without attributes, such as|> H1 - Built-in styling syntax such as

*Elmstatic*and/code/ - An annotated verbatim sequence

`elm-markup`{name} - Annotated sequence

[Highlight.js]{link | url = https://highlightjs.org}which is used to define a link.

One more structure that elm-markup is able to parse is a tree — useful for dealing with nested lists, for example — but I'm not going to demonstrate it here.

The parser for a document with all these elements is composed out of different pieces. Let's start with only handling text with built-in styling:

styledTextToHtml styles str =

Html.span

[ Html.Attributes.classList

[ ( "bold", styles.bold )

, ( "italic", styles.italic )

, ( "strike", styles.strike )

]

]

[ Html.text str ]

inlineMarkup =

Mark.text styledTextToHtml

Mark.text takes a function that defines how a string with some styles attached gets converted into output. Here, we are converting it into a <span> with classes attached to it (which can subsequently be styled with CSS).

Then, we need to create a document, which generally combines multiple parsing elements, although we only have one element (inlineText) for now:

document =

Mark.document (Html.div []) inlineMarkup

The next step is to compile the document with a given markup string. This produces the output, errors, or a combination of both:

case Mark.compile document markup of

Mark.Success html ->

Html.div []

[ stylesheet

, html

]

Mark.Almost { result, errors } ->

-- This is the case where there has been an error,

-- but it has been caught by `Mark.onError` and is still rendereable.

Html.div []

[ stylesheet

, errorsToHtml errors

, result

]

Mark.Failure errors ->

errorsToHtml errors

Before we move on to parsing more complex markup, here is the whole program showing the minimal working elm-markup setup:

module Main exposing (main)

import Html exposing (Html)

import Html.Attributes

import Mark

import Mark.Error

styledTextToHtml styles str =

Html.span

[ Html.Attributes.classList

[ ( "bold", styles.bold )

, ( "italic", styles.italic )

, ( "strike", styles.strike )

]

]

[ Html.text str ]

inlineMarkup =

Mark.text styledTextToHtml

document =

Mark.document (Html.div []) inlineMarkup

main =

let

stylesheet =

Html.node "style" [] [ Html.text css ]

errorsToHtml errors =

Html.pre [] [ Html.text <| String.join "\n" <| List.map Mark.Error.toString errors ]

in

case Mark.compile document markup of

Mark.Success html ->

Html.div []

[ stylesheet

, html

]

Mark.Almost { result, errors } ->

-- This is the case where there has been an error,

-- but it has been caught by `Mark.onError` and is still rendereable.

Html.div []

[ stylesheet

, errorsToHtml errors

, result

]

Mark.Failure errors ->

errorsToHtml errors

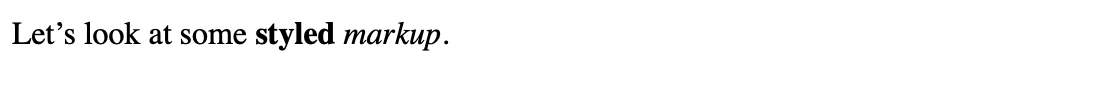

markup =

"""

Let's look at some *styled* /markup/.

"""

css =

"""

.italic {

font-style: italic;

}

.bold {

font-weight: bold;

}

.strike {

text-decoration: line-through;

}

"""

This program will show the following:

Moving on to other markup, let's deal with |> H1, because it's easy, and shows the composition of different pieces:

header1 =

Mark.block "H1" (Html.h1 []) inlineMarkup

Note that the second argument Html.h1 [] is a function which takes a list of Html msg values. The type of inlineMarkup happens to be Block (List (Html msg)) which is why we can use it as the third argument. The other reason to use it is that it allows header text to contain inline styling rather than just plain text.

Now how about the |> Metadata block? Instead of text, it contains a record of keys and values, which we can handle like this:

frontMatter title tagString =

let

tagsToHtml tagStr =

List.map

(\tag ->

Html.span [ Html.Attributes.class "tag" ] [ Html.text tag ]

)

<|

String.split " " tagStr

in

Html.div [] <|

Html.h1 [] [ Html.text title ] :: tagsToHtml tagString

metadata =

Mark.record "Metadata"

frontMatter

|> Mark.field "title" Mark.string

|> Mark.field "tags" Mark.string

|> Mark.toBlock

frontMatter is a straightforward conversion of strings to HTML. The interesting part is in the metadata function, where we use Mark.record to declare that |> Metadata is a specific kind of block. Then we describe the types of each field in the record, and finally finish things off by converting it to a block.

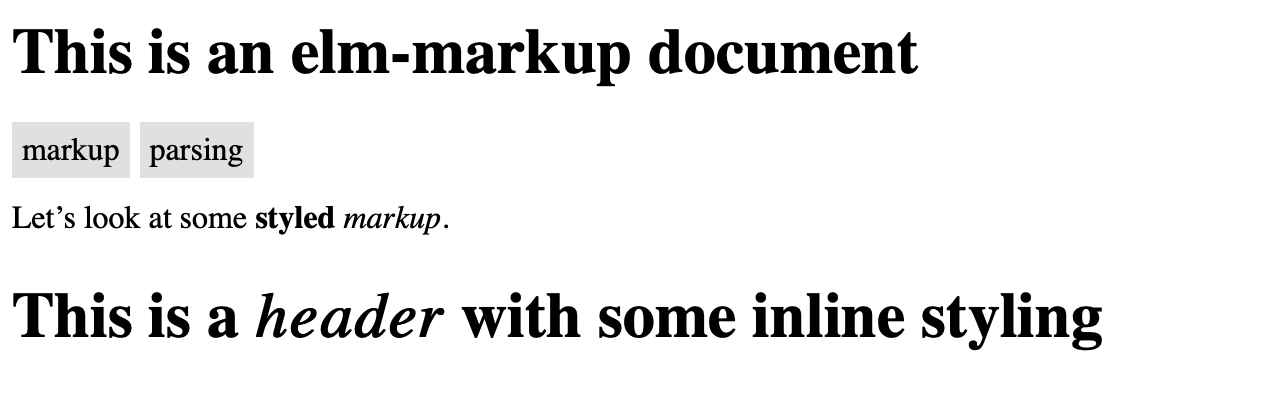

Now, the following markup (with a bit of CSS) will produce the output below:

|> Metadata

title = This is an elm-markup document

tags = markup parsing

Let's look at some *styled* /markup/.

|> H1

This is a /header/ with some inline styling

In similar fashion, we can handle |> Code, converting the code field into a <pre> tag:

code =

Mark.record "Code"

(\lang str ->

Html.pre [ Html.Attributes.class lang ] [ Html.text str ]

)

|> Mark.field "lang" Mark.string

|> Mark.field "code" Mark.string

|> Mark.toBlock

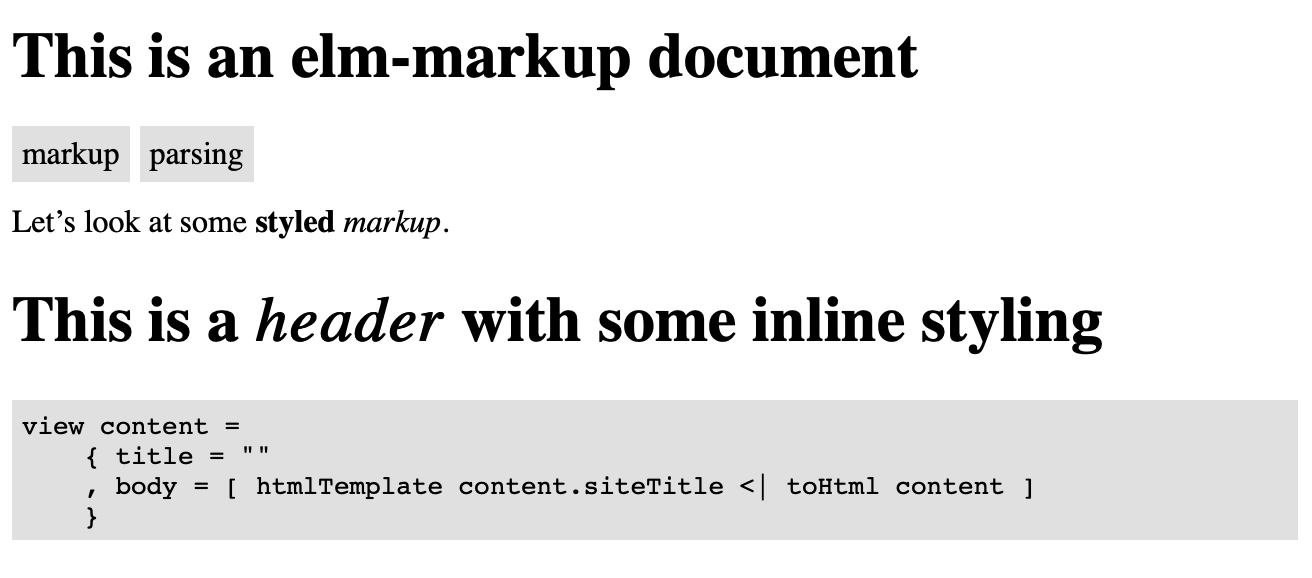

And with a bit of code added to the markup, it shows up in the output:

|> Metadata

title = This is an elm-markup document

tags = markup parsing

Let's look at some *styled* /markup/.

|> H1

This is a /header/ with some inline styling

|> Code

lang = elm

code =

view content =

{ title = ""

, body = [ htmlTemplate content.siteTitle <| toHtml content ]

}

This takes care of a big chunk of the markup, but we still need to handle inline annotations like `elm-markup`{name} and [Highlight.js]{link | url = https://highlightjs.org}. For that, we need to revisit inlineText. Instead of Mark.text, we're going to use the more advanced Mark.textWith:

annotatedInlineMarkup =

Mark.textWith

{ view = styledTextToHtml

, replacements = Mark.commonReplacements

, inlines =

[ Mark.annotation "link"

(\strings url ->

Html.a [ Html.Attributes.href url ] <|

List.map (\(styles, str) -> styledTextToHtml styles str) strings

)

|> Mark.field "url" Mark.string

, Mark.verbatim "name" (\str -> Html.code [] [ Html.text str ])

]

}

Instead of a single function taken by Mark.text, it takes a record. The first field, view, is a function that handles inline styles, so we reuse the already defined styledTextToHtml here. replacements defines a map of character replacements (such as replacing two dashes with an emdash, or straight quotes with curly quotes). We use Mark.commonReplacements which is the default mapping supplied by the elm-markup package.

Finally, inlines is where we are going to deal with inline annotations. The structure of an annotation definition like link above is very similar to how we handled the record in the |> Metadata block. For verbatim annotations, we use Mark.verbatim to wrap the text in <code> tags.

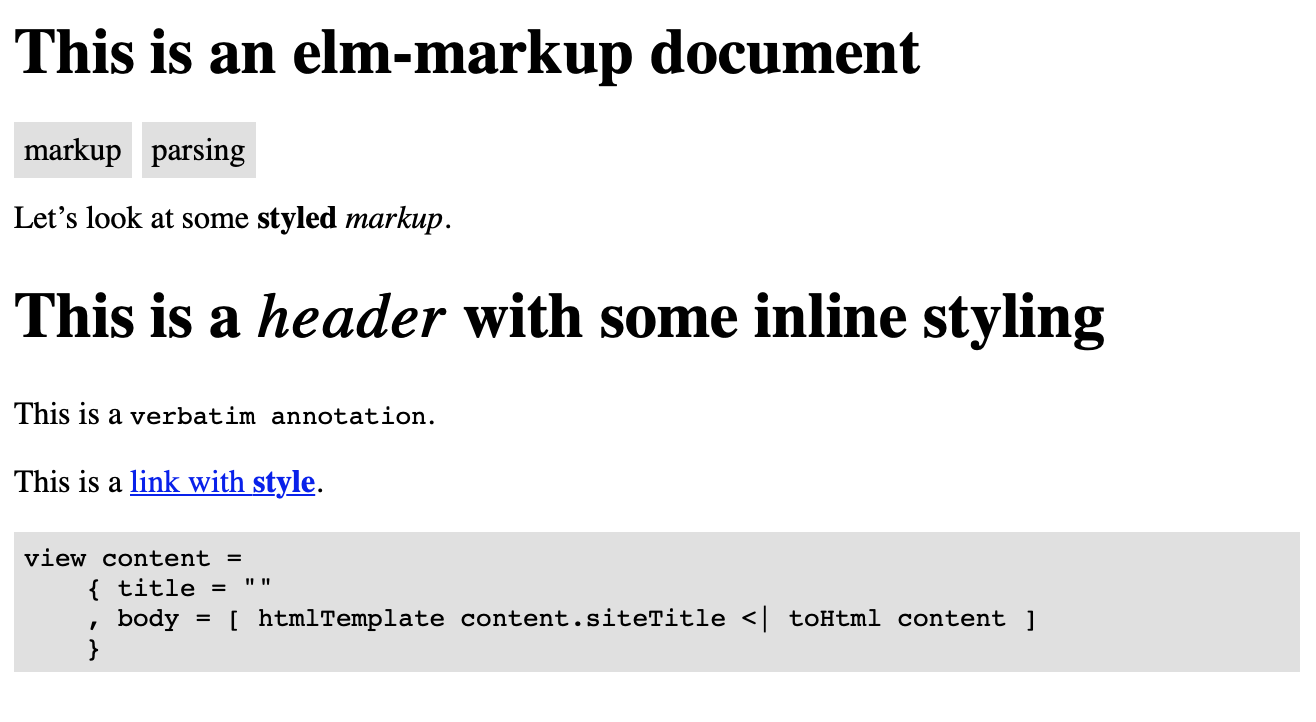

As a result, we can display fairly sophisticated documents:

|> Metadata

title = This is an elm-markup document

tags = markup parsing

Let's look at some *styled* /markup/.

|> H1

This is a /header/ with some inline styling

This is a `verbatim annotation`{name}`.

This is a [link with *style*]{link | url = "#"}.

|> Code

lang = elm

code =

view content =

{ title = ""

, body = [ htmlTemplate content.siteTitle <| toHtml content ]

}

Pretty cool! There is still one wrinkle though, if we just throw all these definitions into Mark.manyOf like this when defining document:

document =

Mark.document (Html.div []) <|

Mark.manyOf

[ metadata

, header1

, code

, Mark.map (Html.p []) annotatedInlineMarkup

]

It means that the |> Metadata block can appear many times throughout the markup, which doesn't really make sense. Can we enforce the rule that it appears only once, at the start of the document? Yes! We need to switch to Mark.documentWith:

metadata =

Mark.record "Metadata"

(\title tags -> { title = title, tags = tags })

|> Mark.field "title" Mark.string

|> Mark.field "tags" Mark.string

|> Mark.toBlock

document =

Mark.documentWith

(\meta body ->

Html.div [] <| (frontMatter meta.title meta.tags) :: body

)

{ metadata = metadata

, body =

Mark.manyOf

[ header1

, code

, Mark.map (Html.p []) annotatedInlineMarkup

]

}

A couple of things to note here:

metadatanow generates a record instead of anHtmlvalue.- The first argument to

documentWithis a function that receives the metadata (the record withtitleandtagsin our case) and the body, which ends up being aList (Html msg)since all our parsing bits generateHtml msgvalues and we combined them withMark.manyOf. - We now use

frontMatterin this function to convert metadata into HTML, instead of using it directly in themetadatawhich we did when metadata was a regular block.

Now, the elm-markup parser will ensure that |> Metadata only appears at the start of a document, and nowhere else. It will fail to parse the markup and return an error in any other case.

That's it! I hope this tutorial helps you understand how to write your own elm-markup parsers. I've made an Ellie showing the complete code for you to play around with.